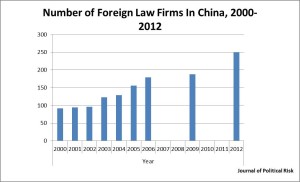

Number of Foreign Law Firms in China, 2000 to 2012. Sources: www.people.com.cn; www.china.findlaw.cn; www.chinanews.com; www.chinalaw.org.cn; www.moj.gov.cn; Fangyuan magazine, issue No.8, 2012; People’s Daily (overseas edition), June 9, 2000.

Journal of Political Risk, Vol. 1, No. 6, October 2013.

By Julian Yulin Yang, Esq.

Abstract: Mr. Julian Yang, a practicing lawyer and arbitrator in Beijing, China, describes problems with the Chinese legal system, including bias by courts, corruption, a culture of litigation, and lack of sufficient numbers of lawyers to satisfy market demand. He argues for legal services reform in China, including: 1) allowing foreign lawyers to address Chinese courts, 2) allowing foreign lawyers to practice commercial law, 3) increasing consultation of lawyers in contractual law to avoid litigation, 4) use of arbitration to decrease the quantity of litigation, 5) increasing the rights of Chinese lawyers, such as rights to gather evidence, and 6) increasing the rights of clients, for example the right to freely choose and meet with lawyers without police scrutiny. Mr. Yang argues that these reforms will increase the influence of China abroad, improve legal services in China, and provide a test as to whether greater political reform would be possible without loss of political stability.

Legal-Services-Reform-in-China-Chinese-Language-Version 2 中国法律服务的改革:局限、政策和战略

Introduction

The key to long-term economic success in China will depend upon at least two major pillars: an effective legal framework and a well-established reputation system. In Chinese, reputation (声誉) refers to a country’s mature degree of trust in its society (which has thousands of years of tradition and enjoyed high esteem in Chinese public opinion). Because of the economic reforms led by the late Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping (beginning in 1978), China opened to foreign direct investment (FDI), instituted market competition, and thereby achieved an economic growth rate sufficiently high to puzzle many economists. A Nobel Prize will undoubtedly be awarded to a scholar who can explain the runaway growth of China, despite what foreign experts and Chinese politicians call “one leg walking”(一条腿走路). The missing leg is political reform. Due to the risk of instability, Chinese leaders have hesitated to democratize further and pursue other political reforms. I argue that legal reform could substitute, at least temporarily, for political reforms, and thereby improve economic performance. Legal reform will toughen the political framework, paving the way for eventual political reforms.

The necessary reforms in the Chinese legal space require reevaluating the legislative, judicial and enforcement functions of government as they apply to lawyers and firms. More specifically, it refers to changes and adjustments to laws and regulations governing economic activities in China. Without agreement and approval of the People’s Congress, the implemented laws cannot be changed. Without agreement and approval of the State Council or its authorized organs, no nationwide regulations can be changed. Therefore, a concrete change in legal matters will bring about subtle changes in the central nervous system of the political structure. Thus legal reform is the best tool to implement a deeper level of openness and political reform that will at the same time avoid social and political turmoil. It will serve as a useful test as to how China can enact reforms and remain stable.

Limits on the Practice of Law by Foreigners

Though over a decade passed since the World Trade Organization (WTO) admitted China, the country still severely limits the practice of law by foreign firms. All China-related legal services, non-litigation or litigation, legal opinions or legal explanation, are forbidden territory for foreign law firms in China.[1] Foreign law firms cannot hire local lawyers.[2] Hired local assistants are barred from providing China-related legal services to clients.[3] For example, New York-based law firm A is forbidden to establish subsidiary B in the name of a consulting firm in China to provide China-related legal services, even if the subsidiary is a pure law office.[4] Chinese law forbids foreign law firms from merging with, or acquiring Chinese law firms.

In addition, the Chinese government has erected a firewall between foreign law firms and itself. Foreign lawyers may not appear in the courtroom to make a point. They may not involve themselves with trials that have national security or stability implications. The punishment for those who dare to cross the line is severe, as such acts are perceived as endangering the legal system.[5] If such evidence is found to threaten the national security, public safety, or social order, the involved foreign law representative may face criminal charges. Another example: if a foreign law office in China hires local lawyers, it will first receive a warning from the Chinese authority. If no correction is made by the foreign law office, its certified license may be revoked. Indeed, before trials of any sensitive criminal cases, Chinese lawyers receive messages from the government stating, “No foreign law firms should be involved,” and, “stay away from this dissident.” This standard protocol is very effective because all Chinese law firms must be registered and obey the government authority.

Foreign law firms may only address issues of international commerce and act as the representative of foreign clients to Chinese law firms. Foreign law offices have found only indirect ways to practice law in China, such as: providing clients with information on international laws, regulations, and conventions; representing foreign clients in the assignation of Chinese law firms to conduct China-related legal cases; and, signing contracts with Chinese law firms to maintain a long-term consignment relationship.[6] Allow me to return to the aforementioned example: a Beijing subsidiary of a New York-based law firm. This office can represent its foreign clients and refer its foreign clients (often a US company in China) to a local Chinese law firm to work on the case. All open formalities and appearances are enacted by the Chinese firm. Yet, the New York firm remains behind the scenes during this exchange. Then, the two firms share the legal fees. Chinese authorities tolerate this arrangement as long as it is for a purely commercial civil case.

Some foreign firms guide the entire process of a commercial litigation trial, except for addressing the judge, for which they liaise with a Chinese law firm. For commercial law with a foreign -related case, a foreign law firm may control investigation of the case, a procurement of evidence, and provision of legal opinions.[7] Foreign law firms must study Chinese laws and regulations in order to provide their clients with legal services in China. However, they are not allowed to provide these opinions to the court. Currently, foreign law firms are doing their best to provide clients with legal services in the confused legal environment of China by, according to the Chinese proverb, “crossing the river by feeling the stones” (摸着石头过河).

These limits are said to protect the market share of Chinese lawyers in domestic legal services. Based on statistics from the Law Society of China, there were 263 representative offices of foreign law firms in 2012, from 21 countries.[8] If free competition were allowed, goes the protectionist argument, foreign giants would soon occupy the market for domestic legal services, and Chinese lawyers would likely lose market share. However, this stated reason masks the primary reason. If foreign law firms provide domestic legal services, they could acquire sensitive information and influence domestic politics. Foreign involvement in certain types of criminal trials, including corruption and other “illegal activities” of high-ranking government officials, would put the Chinese government into an embarrassing situation. This would threaten core interests of national security and stability. In the past, neither side of the ruling party has accepted, much less promoted, such reforms to open the legal service industry to foreign competition.

Present Situation of Chinese Law Firms

Before economic reform, very few lawyers existed in China. In 1979, only 212 lawyers practiced law.[9] There must have been even fewer during the “Cultural Revolution,” when all law firms closed. Few would have foreseen the growth of the legal industry to approximately 230,000 lawyers in 2012[10] and 19,361 law firms on January 1, 2013.[11] But with a country of population 1.3 billion, there is still only one lawyer per 5,700 persons. Compare this to the more than 1 million lawyers in the United States, yielding one lawyer per 260 persons.[12]

China’s economic growth has outpaced Chinese growth in the legal profession, leading to market inefficiencies. For instance, before economic reforms, most Chinese citizens were not allowed to own private homes and vehicles. Now, after more than 30 years’ accumulation of assets, a wealthy middle class has formed and owns not only houses and vehicles, but complicated investment properties, equities, and debts. Therefore, the legal services demand has increased for family assets, estate planning, commercial investment, technical transfer, joint ventures, properties, equities and debt.

Protection of the domestic legal industry has until now made the small number of Chinese lawyers very wealthy, but at the expense of quality, availability, and the consumer’s pocketbook. Chinese legal services are weak in quantity, quality, accumulation of assets, foreign-related legal practices, and large international deals. But if China welcomes foreign lawyers into the domestic legal services market, Chinese law firms will learn, strengthen from competition, and be able to export legal services and even political influence to other countries. In fact, China’s best strategy is to self-improve, even through piecemeal participation in the international market. Thereby, China increases the business of its legal services market. Given the success of China’s other exports and the positive result of global free trade, it is surprising that China is taking a conservative attitude, rather than proactively expanding and seeking foreign involvement for its legal services industry.

China Needs to Improve Its Reputation In the Legal Field

While the lack of a matured legal system is highly problematic for China’s development, the lack of mutual trust in the legal field is worse. The practice of law in China is plagued by corruption, criminality, and unethical business practices. What reaches the headlines on non-legal business matters are the wanton rupture of contracts and outright business deceit. All have complicity among lawyers and corollaries in the legal services industry. Many in the Chinese legal industry seek unethical shortcuts to make money, rather than focusing on improving reputation. This engenders legal mistrust, which is akin to throwing sand into the engine of economic growth.

Both locals and foreigners suspect that Chinese courts are biased in favor of Chinese litigants. Foreigners are more suspicious because they don’t trust Chinese authorities in the first place. If Chinese litigants are not well-connected, and lack authority, they should also expect unequal treatment before the law. Especially regarding litigation between private and public entities, the close affiliation of Chinese courts with the government in terms of financial control and personnel appointment makes it nearly impossible for courts to make unbiased decisions about their superiors.

Can foreign and local businesses trust Chinese judges? During trials, are we sure the presiding judge has not taken bribes? Are judges partial to one side? How can we know whether trial judges did not receive orders from their superiors to influence a decision? Though in some cases a “people’s juror” appears in the courtroom, it is well-known that jurors normally follow the judge’s tone in their decisions. Chinese judges and juries are in no way comparable to their Western counterparts in independence of judgment.

Money and networks determine a substantial number of court rulings, especially in the local People’s courts. Some litigants make every effort to buy judgments with cash. The difficulty is that they rarely discover how much the other side has put into the court battle. The more effective way to influence the court’s decision is for the lawyer to use his or her reciprocal relationships or social capital, known as guan-xi (关系). One of the key elements in deciding which lawyer to hire is the strength of his or her guan-xi, as this attribute is the lawyer’s primary competitive tool.

Neglect Of Non-Litigation Legal Services

Lawyers from small and medium-sized law firms in China typically greet each other by saying, “with what type of case are you busy now?” Unfortunately, “case” in this context refers to litigation, the only difference being civil or criminal. Most Chinese legal services involve litigation; this is an unhealthy phenomenon. In combating cancer, prevention is more effective than late-stage treatment. Similarly in operations, investments, mergers, acquisitions, and public offerings, the avoidance of legal risk through legal opinions and mediation are all preferable to litigation.

In Western countries, especially in larger-sized law firms, non-litigation services are the larger share of legal business. Chinese law firms should seek a similar balance. The reason for over-litigation rather than prevention is that most clients in China, chief executive officers (CEOs) in particular, do not trust their lawyer’s opinion. They do not feel at early stages of potential conflicts that they need or can afford legal consultation. Only when they are facing court trials do they hire lawyers. Furthermore, following Chinese historical and cultural tradition, clients seek legal consultation directly from judges rather than lawyers. Clients may not like the judge, but they must follow state authority represented by the judge. Lawyers, on the other hand, are simply civic individuals. Their opinions have no binding force.

The Need for Reform in Foreign Commercial Legal Services, Arbitration, and the Rights of Lawyers and Clients

Reforms within foreign commercial legal services are necessary, and there are several ways the industry could be improved. In commercial trials, the People’s Court should implement sole jurisdiction through strict independence and impartiality of rulings. Since the interference from the superior government is the main threat to the Courts’ jurisdiction, the government should pass laws to increase the independence of courts from the institutional system of government control. The separation of courts from government organs should include budget control, personnel appointment and operational guidelines. In short, courts should be a purely technical organ to handle trials. The latest challenge is the verdict for trial of BO Xilai, a former Politburo member of the Communist Party of China (CCP). Will the decision be made in-court or in the Politburo?

There are some exceptions to political influence over the courts. The General Customs Administration of China is an example of independence. They report directly to leadership of the State Council, and independently handle anti-smuggling cases with very little political influence.

Since foreign law firms have in fact participated in domestic commercial legal services, albeit indirectly and in a highly limited manner, the only missing part is a confirmation of law and regulations towards this practice. The national authority needs to rewrite its laws to confirm that foreign law firms enjoy equal opportunity to represent Chinese clients in commercial legal cases. Some say China will fully open its legal market to foreigners in 2015.[13] I doubt it. I don’t think Chinese authorities are prepared for a full opening of China’s legal market, both for political stability considerations and for protection of fellow lawyers. But, there is no question that the Chinese government should open the legal services market to foreign law firms as soon as possible. For practical purposes, it should first open commercial legal services to foreign firms. This will allow foreign law firms to practice law and enjoy equal status with their Chinese counterparts in commercial cases. It will improve competition and make legal services more attractive to clients, without touching sensitive areas of the political structure and without threatening political stability. If the experiment works, just like Deng Xiaoping decided to set up Shengzhen city as an experimental zone more than 30 years ago, it will pave the way for a full legal market opening.

China should strengthen the role of commercial arbitration, which has several advantages when compared to court judgments. Arbitration reduces heavy burdens carried by courts. Because of the non-governmental nature of arbitration in China, arbitration is less biased and less subject to political influence, as compared to court judgments. The government should pass a law to grant arbitration institutions independence of budget control and daily operation. The government should welcome arbitration, as every court case involves risk. If the case is decided badly, or corruption is made public by the court, the government’s reputation is tarnished. On the other hand if arbitration yields a bad judgment, the government will not bear the blame. The number of cases, trials, and judgments accepted by courts should be gradually decreased as arbitration gains caseloads. At the same time, the binding force of adjudications issued by arbitration tribunals should be strongly recognized by law. The punishment for neglecting such adjudications should be commensurate with the public harm of not having arbitral commissions.

The government should encourage Chinese and foreign arbitrators to jointly form arbitration tribunals for domestic commercial dispute cases. Foreign lawyers who represent their clients should be allowed to present legal opinions to arbitrators in China. Involvement of foreign law firms in China’s arbitration industry will improve the quality and supply of arbitration services.

Chinese lawyers need to have more rights when practicing law. Compared to other enforcement professionals, namely judges, public prosecutors, and police, lawyers have the fewest professional rights. Limited professional rights have hindered quality client service. Specifically, it is necessary to give lawyers the right to meet independently with suspects without police scrutiny, and investigate and obtain evidence. Clients should be able to choose their lawyers without government interference.

Conclusion

Optimizing economic growth in China requires legal services reform. Not only will this reform serve as a bellwether for broader political reform; it will increase the quality and availability of legal services both in China and in other parts of the world. For practical purposes, allowing foreign law firms to practice China-related commercial legal cases will be a breakthrough for the current lackluster situation.

Mr. Julian Y. Yang is Managing Director of the Tian-ji Law Firm in Beijing, China. He is an arbitrator with the Beijing Arbitration Commission. He has a Master’s of Public Administration from Harvard University, and was a visiting scholar at Harvard Law School. Dr. Anders Corr and Ms. Samantha Gay served as editors for this article. The Journal of Political Risk is published by Corr Analytics, a New York based political risk consultancy.

JPR Status: Working Paper.

[1] Article 15; Qin Jing. “Administrative Regulations on Representative Offices of Foreign Law Firms in China.” Ministry of Justice, People’s Republic of China (PRC), http://www.moj.gov.cn/lsgzgzzds/content/2008-07/21/content_905354.htm?node=278, accessed September 25, 2013.

[2] Page 296; The American Chamber of Commerce in the People’s Republic of China. American Business in China. Beijing: American Chamber of Commerce in the People’s Republic of China, 2011.

[3] Article 16; Qin Jing. “Administrative Regulations on Representative Offices of Foreign Law Firms in China.” Ministry of Justice, PRC. http://www.moj.gov.cn/lsgzgzzds/content/2008-07/21/content_905354.htm?node=278, accessed September 25, 2013.

[4] Article 24; Qin Jing. “Administrative Regulations on Representative Offices of Foreign Law Firms in China.” Ministry of Justice, PRC. http://www.moj.gov.cn/lsgzgzzds/content/2008-07/21/content_905354.htm?node=278, accessed September 25, 2013.

[5] Article 6; Qin Jing. “Administrative Regulations on Representative Offices of Foreign Law Firms in China.” Ministry of Justice, PRC. http://www.moj.gov.cn/lsgzgzzds/content/2008-07/21/content_905354.htm?node=278, accessed September 25, 2013.

[6] Article 15; Qin Jing. “Administrative Regulations on Representative Offices of Foreign Law Firms in China.” Ministry of Justice, PRC. http://www.moj.gov.cn/lsgzgzzds/content/2008-07/21/content_905354.htm?node=278, accessed September 25, 2013.

[7] Hailong, Quan. “Present Features of Foreign Law Firms in China.” Fanyuan Lvzheng, November 8, 2012.

[8] Unspecified Editor. “China Currently Has 230,000 Practicing Lawyers.” Xinhua. http://chinapeace.org.cn/2012-06/26/content_8075874.htm.

[9] Guimong, Liu. “30 Years After Reestablishment of the Lawyer System in China.” Liu Guiming’s Blog. http://blog.sina.com.cn/sky12355, accessed September 25, 2013.

[10] Unspecified Editor. “China Currently Has 230,000 Practicing Lawyers.” Xinhua. http://chinapeace.org.cn/2012-06/26/content_8075874.htm

[11] Qin Jing. “Department of Directing Lawyers and Notarization.” Ministry of Justice, PRC. http://www.moj.gov.cn/lsgzgzzds/content/2010-12/10/content_3000044.htm?node=278, accessed September 25, 2013.

[12] Qin Jing. “Department of Directing Lawyers and Notarization.” Ministry of Justice, PRC. http://www.moj.gov.cn/lsgzgzzds/content/2010-12/10/content_3000044.htm?node=278, accessed September 25, 2013.

[13] Hailong, Quan. “Present Features of Foreign Law Firms in China.” Fanyuan Lvzheng, November 8, 2012.