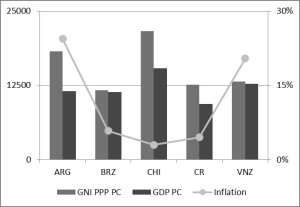

Figure 1: Economic data for Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica and Venezuela. Sources: Worldbank 2012, Index Mundi and Agencia Brasil.

Journal of Political Risk, vol. 1, no. 3, July 2013.

Over the last twelve months, it would seem that the habitants of Latin America and the Caribbean are particularly adept at protesting against their leaders and institutions, especially in Brazil, Chile and Costa Rica. Over a one-year period, Brazilian, Chilean and Costa Rican government officers witnessed hundreds of thousands of citizens protesting issues such as crime, corruption, and the lack of low-cost quality public services.

Although there are many differences among the movements, the similarities are striking. First, protesters target problems that have significant impact in their lives: education, transportation and political inefficiency. Second and counter-intuitively, those countries have all enjoyed economic booms recently. Finally, all three countries face important elections in the near-term future. Table 1 shows several characteristics of the protest movements in the three countries.

| Brazil | Chile | Costa Rica | |

| Trigger issue that ignited the protests | Raise in public transportation fares | Demand for public investment in secondary and university education, opposition to goldmine and hydroelectric projects | Demand for the resignation of environment minister |

| Deeper issues that sustained the protests | Lack of trust in government institutions, high levels of corruption, low quality of state-provided services, high living & transportation costs, increase of inflation, runaway costs of 2014 World Cup | Deep discontent over increase of inequality | Elimination of benefits for public workers, annulment of public concession law |

| Political scenario | Presidential, congressional and gubernatorial elections in 2014 | Presidential elections in November, 2013 | Presidential, congressional and gubernatorial elections in 2014 |

| Economic scenario | Very low GDP growth, increase in inflation, low unemployment, growing middle class | Economic boom, growing middle class, eradication of poverty, free-market economic policies that increase inequality | GDP growth, low inflation, some unemployment |

| Average personal tax rate | 36.5% | 26.5% | 24.2% |

| Impact on economy | Little reduction in spending from consumers and investment from corporations | Short-term: little reduction in spending from consumers and investment from corporations;Mid-Long term: reduction of GDP growth if energy-hungry Chile does not build necessary dams | Little reduction in spending from consumers and investment from corporations |

| Response from Government | Awkward: plebiscite for a constitutional change, a topic not demanded by protesters | Wishful thinking: Promise of a constitutional change, a topic supported by few Chileans | Reactive: withdraw a bill that restricts strikes in the public sector |

| What has changed so far | Reduction in some transportation fares, imprisonment of a corrupt congressman, increase in educational budget, increase in transparency of public expenditures | Chilean Senate approved a bill that would prohibit indirect or direct state support of for-profit educational institutions in order to invest in public education. | Resignation of CEO of state-owned oil refinery |

| Movement leadership and profile of participants | No clear leadership; broad-based support from low to mid-high class | Student organizations; secondary and undergraduate level students | Student organization and teachers´ unions; workers and undergraduate-level students from University of Costa Rica, high school teachers´ unions |

Table 1: Main characteristics of protests in Brazil, Chile and Costa Rica. Source of average personal tax rate: KPMG´s Individual income tax and social security rate survey 2012. [1]

The velocity with which the protests spread throughout Latin America is surprising, however, the reasons for these movements are not. In Brazil, the quality of public services is painfully low, while federal government has been unable to support economic growth. Brazil transfers more than one third of national wealth to the three levels of government (Table 1) while the Brazilian population does not receive the equivalent in services provided by the government. In Chile, the population is distressed by increasing economic inequality. New fiscal discipline, in the form of benefits elimination for public workers, fuels protests in Costa Rica.

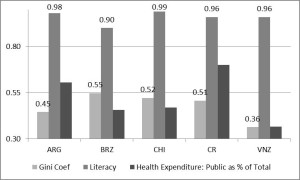

Argentinians and Venezuelans face high inflation (See Figure 1), and generally dislike their public institutions, but do not have significant volumes of protest activity. The main reason can be seen in Figure 2, which shows that the Gini coefficient (a measure of economic inequality) is low in both countries. In addition, both Argentina and Venezuela possess high literacy rates and, in Argentina´s case, high expenditures in public health. As a conclusion, the social tensions are currently lower in Argentina and Venezuela than in Brazil, Chile and Costa Rica. One will need to see these two countries become more unequal or less supportive of their populations to witness protests in in the streets of Buenos Aires and Caracas similar to those seen in São Paulo, Rio, Santiago de Chile and San José.

Figure 2: Gini coefficient, literacy and public health expenditure as % of total expenditure. Sources: Worldbank 2012 and Index Mundi.

The impact of the protests on the economy of each country will be negative. In the short-term, there will be a reduction in consumer spending because of lower labor productivity and increased transaction costs of operation during instability. Investors will delay investments until they understand the scope and scale of the changes that arise from the social movements. A significant portion of investors will divert investments to other more stable countries. Interest rates will experience upward pressure, as lenders feel less secure in politically unstable environments. However, long-term improvements on social movement goals, such as decreased corruption and increased income equality, will improve political stability. If measures to achieve political stability are not too costly in terms of government expenditure, investments will again flow into these countries.

Unlike the Arab Spring, the protests in Latin American do not threaten to overturn the current democratic system. Dissatisfaction with the mismanagement of public resources may eventually lead to changes of public officers, but Brazilians, Chileans and Costa Ricans will do so through regular elections, already scheduled. As a consequence, the increase in political risk from the social movements in Latin America is low as compared to the countries seized by the Arab Spring.

Mr. Evodio Kaltenecker holds an MBA from Harvard Business School (2001), and is a Professor at the BBS Business School, São Paulo, Brazil.

Peer review status: 3/3 (Complete)